Nils Anders Tegnell (17 April 1956) is the current state epidemiologist of Sweden, specialized in infectious diseases. He had key roles in the Swedish response to the 2009 swine flu pandemic and the COVID-19 pandemic. During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, Tegnell’s Public Health Agency of Sweden opposed lockdowns and recommending face masks for general use.

Tegnell has no doubts about lockdowns on a national scale: “It’s really using a hammer to kill a fly”. Instead, his approach has been about having a strategy that can work for years if needs be, rather than the constant chopping and changing seen in the rest of Europe. “We don’t see it as viable to have this kind of drastic closing down, opening and closing. You can’t open and close schools. That is going to be a disaster. And you probably can’t open and close restaurants and stuff like that either too many times. Once or twice, yes, but then people will get very tired and businesses will probably suffer more than if you close them down completely,” he says. Sweden’s controversial herd immunity approach to tackling Covid-19 initially ran into high casualties due to poor performance of nursing homes. Sweden therefore ranks fifth-highest in Europe’s per capita death rate (along with other poor nursing-performing countries), but first in the fast downward trend of its infection rates. Norway and Denmark both relaxed their restriction policy during the second half of 2020, on the basis of the Swedish results.

Tegnell warns that a vaccine —if and when it comes— will not be the “silver bullet”. About that vaccine he said in September 2020: “Once again, I’m not very fond of easy solutions to complex problems and to believe that once the vaccine is here, we can go back and live as we always have done. I think that’s a dangerous message to send because it’s not going to be that easy.”

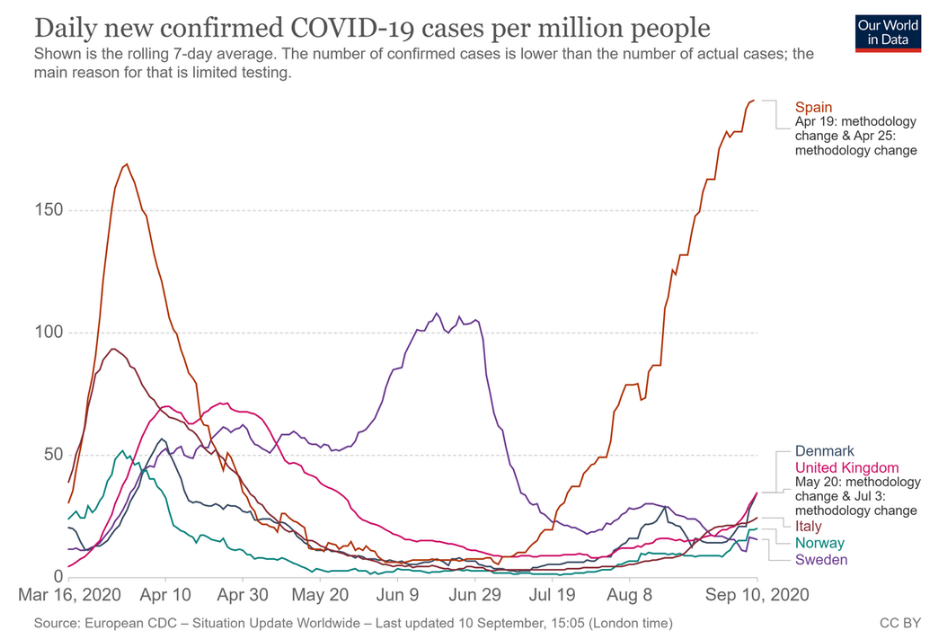

Rolling 7-day average of daily reported covid cases per million people. Note that the lethality of covid has dropped drastically since its first appeared: towards the end of 2020, it is comparable to the lethality of a strong flu.

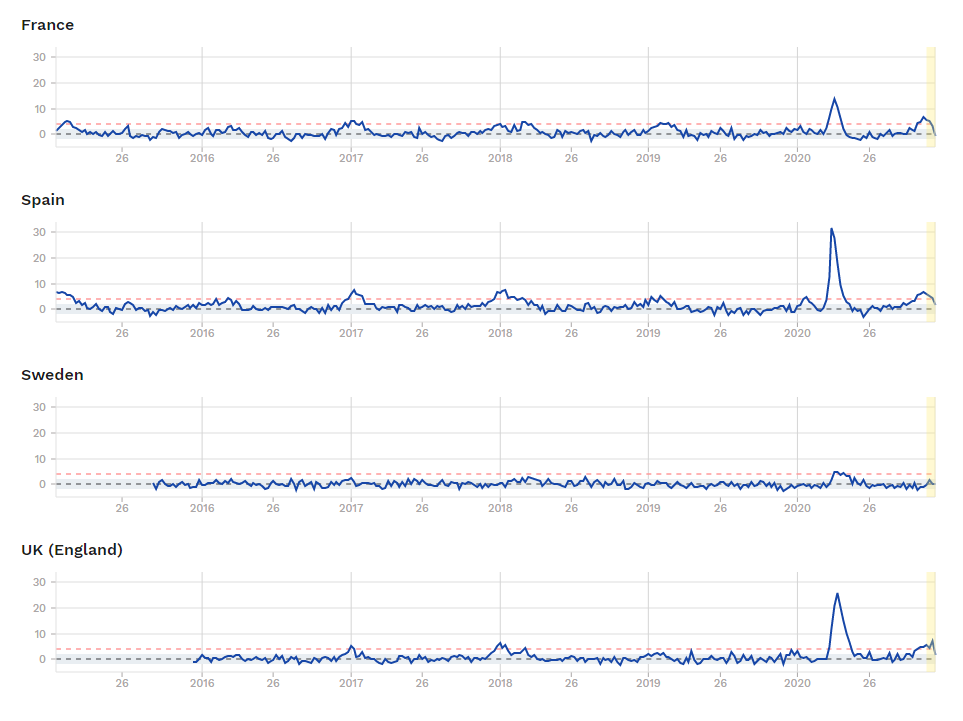

Euromomo’s Excess Death data (age category 65-74) are shown below. The age category 15-44 shows essentially nothing, and the age category 45-64 about half the values of the 65-74 age category. The reason that Spain, UK and Italy were so heavily hit, is mainly due to the nursing homes, and due to their strictly following the medical WHO guidelines. Notably, none of the four selected countries show that mythical “second wave”: simply compare the winter of 2020 with that of 2017, and you should deduce that all the testing positives are false positives, in full agreement with the expectations.

Euromomo has its baselines wrong. With a correct baseline (one that corresponds to the average deaths over the past years), the winter deaths would disappear, and there would be no ‘second wave’. Horrible to say so, but the second wave is nothing else but a misrepresentation of the data. The winter peak visible in Euromomo’s ‘excess deaths’ (misnomer for ‘deaths minus an arbitrary baseline’) represents nothing but ordinary flu.

The absolute number of deaths cannot be manipulated, unless one willingly alters the data, which is fairly easy to prove. The excess number of deaths is liable to misrepresentation, because the baseline can be chosen at will. If the baseline is chosen scientifically, there is but one option: it should identify with the average of the absolute number of deaths over a given temporal window (which should be mentioned by the organism or individual who presents the data). Euromomo conspicuously fails to mention how it determines its baselines. It further troubles interpretation of the data by displaying an obscurely scaled quantity on the vertical axis, instead of a clearly scaled quantity (as is the number of deaths per million inhabitants, which again would be the scientifically obvious candidate). The data on the reported infections are most liable to manipulation: they depend not only on the number of tests, but also on the testing threshold. Lowering the threshold diminishes the number of false positives, and increasing the threshold diminishes the number of false negatives. For no single test package are the fractions of false negatives and positives accurately known.

Interview with Anders Tagnell in Nature, by Marta Paterlini

As much of Europe imposed severe restrictions on public life last month to stem the spread of the coronavirus, one country stood out. Sweden didn’t go into lockdown or impose strict social-distancing policies. Instead, it rolled out voluntary, ‘trust-based’ measures: it advised older people to avoid social contact and recommended that people work from home, wash their hands regularly and avoid non-essential travel. But borders and schools for under-16s remain open — as do many businesses, including restaurants and bars.

The approach has sharp critics. Among them are 22 high-profile scientist, who last week wrote in the Swedish newspaper Dagens Nyheter that the public-health authorities had failed, and urged politicians to step in with stricter measures. They point to the high number of coronavirus deaths in elder-care homes and Sweden’s overall fatality rate, which is higher than that of its Nordic neighbors — 131 per million people, compared with 55 per million in Denmark and 14 per million in Finland, which have adopted lockdowns.

Can you explain Sweden’s approach to controlling the coronavirus?

I think it has been overstated how unique the approach is. As in many other countries, we aim to flatten the curve, slowing down the spread as much as possible — otherwise the health-care system and society are at risk of collapse. This is not a disease that can be stopped or eradicated, at least until a working vaccine is produced. We have to find long-term solutions that keeps the distribution of infections at a decent level. What every country is trying to do is to keep people apart, using the measures we have and the traditions we have to implement those measures. And that’s why we ended up doing slightly different things. The& Swedish laws on communicable diseases are mostly based on voluntary measures — on individual responsibility. It clearly states that the citizen has the responsibility not to spread a disease. This is the core we started from, because there is not much legal possibility to close down cities in Sweden using the present laws. Quarantine can be contemplated for people or small areas, such as a school or a hotel. But [legally] we cannot lock down a geographical area.

What evidence was this approach based on?

It is difficult to talk about the scientific basis of a strategy with these types of disease, because we do not know much about it and we are learning as we are doing, day by day. Closedown, lockdown, closing borders — nothing has a historical scientific basis, in my view. We have looked at a number of European Union countries to see whether they have published any analysis of the effects of these measures before they were started and we saw almost none. Closing borders, in my opinion, is ridiculous, because Covid-19 is in every European country now. We have more concerns about movements inside Sweden. As a society, we are more into nudging: continuously reminding people to use measures, improving measures where we see day by day the that they need to be adjusted. We do not need to close down everything completely because it would be counterproductive.

How does the Swedish Public Health Agency make decisions?

Around 15 people from the agency meet every morning and update decisions and recommendations according to the data collection and analysis. We talk to regional authorities twice per week. The big debate we are facing right now is around care homes for older people, where we registered very unfortunate outbreaks of the corona virus. This accounts for Sweden’s higher death rate, compared with our neighbors. Investigations are ongoing, because we must understand which recommendations have not been followed, and why.

The approach has been criticized for being too relaxed. How do you respond to these criticisms? Do you think it risks people’s lives more than necessary?

I do not believe there is that risk. The public-health agency has released detailed modelling on a region-by-region basis that comes to much less pessimistic conclusions than other researchers in terms of hospitalizations and deaths per thousand infections. There has been an increase, but it is not traumatic so far. Of course, we are going into a phase in the epidemic where we will see a lot more cases in the next few weeks — with more people in intensive-care units — but that is just like any other country. Nowhere in Europe has been able to slow down the spread considerably. About schools, I am confident they are going to stay open on the national level. We are in the middle of the epidemic and, in my view, the science shows that closing schools at this stage does not make sense. You have to shut down schools fairly early in the epidemic to get an effect. In Stockholm, which has the majority of Sweden’s cases, we are now close to the top of the curve, so closing schools is meaningless at this stage. Moreover, it is instrumental for psychiatric and physical health that the younger generation stays active.

Researchers have criticized the agency for not fully acknowledging the role of asymptomatic carriers. Do you think asymptomatic carriers are a problem?

There is a possibility that asymptomatics might be contagious, and some recent studies indicate that. But the amount of spread is probably fairly small compared to people who show symptoms. In the normal distribution of a bell curve asymptomatics sit at the margin, whereas most of the curve is occupied by symptomatics, the ones that we really need to stop.

Do you think the approach has been successful?

It is very difficult to know; it is too early, really. Each country has to reach ‘herd immunity’ [when a high proportion of the population is immune to an infection, largely limiting spread people who are not immune] in one way or another, and we are going to reach it in a different way. There are enough signals to show that we can think about herd immunity, about recurrence. Very few cases of re-infection have been reported globally so far. How long the herd immunity will last, we do not know, but there is definitely an immune response.

What would you have done differently?

We underestimated the issues at care homes, and how the measures would be applied. We should have controlled this more thoroughly. By contrast, the health system, which is under unusual pressure, has nevertheless always been ahead of the curve.

Are you satisfied with the strategy?

Yes! We know that COVID-19 is extremely dangerous for very old people, which is of course bad. But looking at pandemics, there are much worse scenarios than this one. Most problems that we have right now are not because of the disease, but because of the measures that in some environments have not been applied properly: the deaths among older people is a huge problem and we are fighting hard. Moreover, we have data showing that the flu epidemic and the winter norovirus dropped consistently this year, meaning that our social distancing and hand washing is working. And with the help of Google, we have seen that the movements of Swedes have fallen dramatically. Our voluntary strategy has had a real effect.