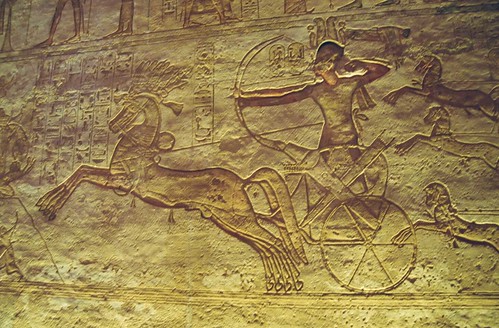

Egyptian chariots were introduced by the Hyksos dynasties (1720-1550 BC), and routinely used from the 18th dynasty onwards. Hyksos chariots had four-spoke wheels. In the late 16th century BC, Egyptians introduced six- and eight-spoke wheels. During a period of one century, all three spoke multiplicities coexisted, after which the four-spoke wheels fell in disuse. The axle moved backward, and the chariot basis inclined forward. This reduced the odds for drivers to fall off the chariot backwards, in case of heavy blows. The back side was permanently open, for rapid ascent and descent during battle.

Archaeology shows a continuous Asiatic presence at Avaris (presently Tell el-Dab’a) for over 150 years before the beginning of Hyksos rule, with gradual Canaanite settlement beginning there around 1800 BC (during the Twelfth Dynasty). It is astonishing that the only argument against identifying the Hyksos with the Israelites from Joseph to Moses, even among prominent Egyptologists (e.g. Manfred Bietak, who discovered the typical four-room structure of Israelite family houses at Avaris), is merely the fact that the accounts of the Bible are not to be trusted. This seems just as silly as the stance of creationists, who hold that scientific insights are not to be trusted, whenever they contradict their interpretation (sometimes ridiculously literal) of the Scriptures.

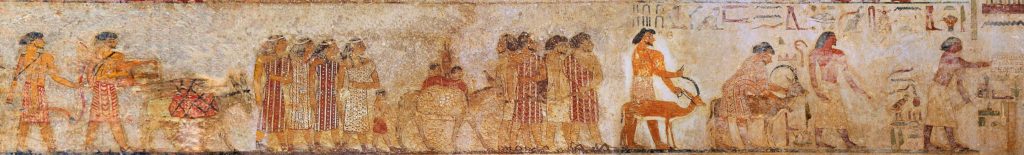

Wall painting from the tomb of 12th-dynasty official Khnumhotep II, at Beni Hasan, dated about 1890 BC: It illustrates a group of Western-Asiatic foreigners, labelled as Aamu (ꜥꜣmw), including the leading man (somewhat inclined, indicating submission) with a Nubian ibex labelled as Abisha the Hyksos (𓋾𓈎𓈉 ḥḳꜣ-ḫꜣsw, Heqa-kasut for “Hyksos”). The first two men at the right are Egyptians.

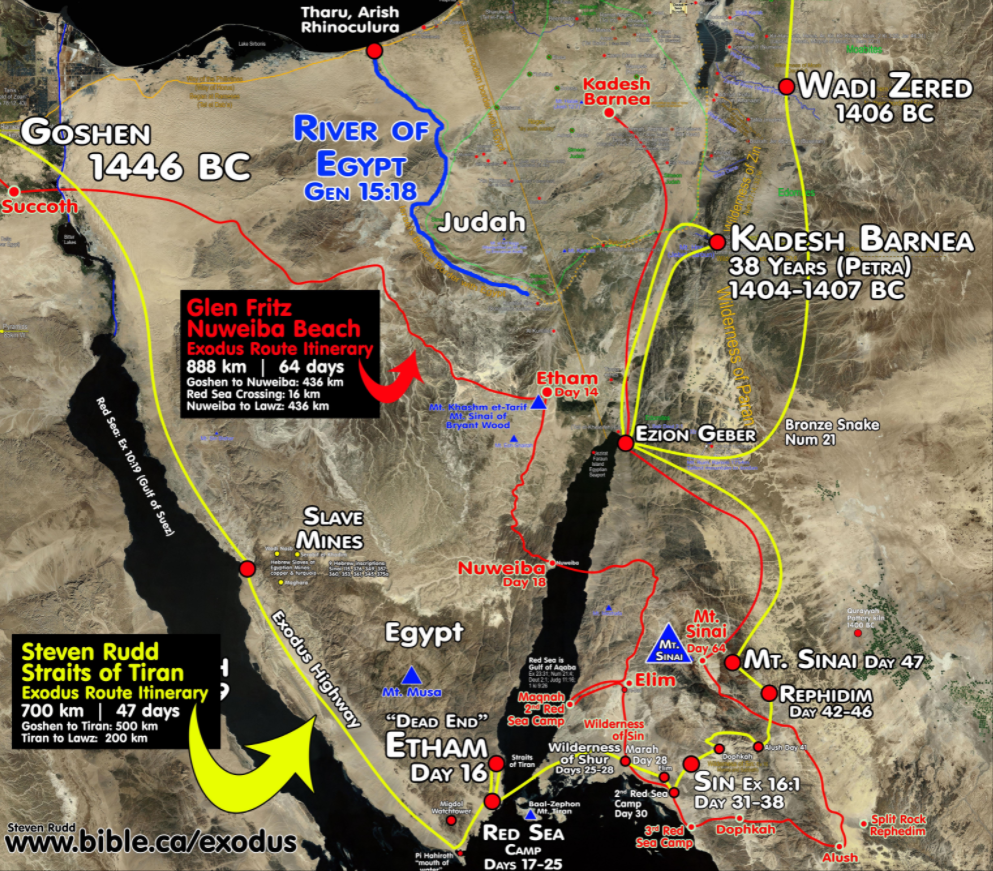

This blog is inspired by the lack of consensus concerning Moses’ exodus route among Christian archeologists. The two main proposals are those of Ron Wyatt and of Steve Rudd. A principal argument in favor of Rudd’s route is that the Nuweiba crossing (Wyatt’s proposal) is three times as deep as the Tiran crossing (Rudd’s proposal). However, the slopes are equal, if not in favor for the Nuweiba crossing. Although I am not an expert in miraculous sea crossings, I suppose that the viability of Moses’ crossing depended much more on the solidity of the sea bottom (Exodus 14: 21-22), than on its depth: 40 cm of mud suffices to make a crossing impossible. Even a fiercely blowing overnight wind cannot dry such a mud layer (Exodus 14: 25). In their 2006 documentary Exodus Decoded, Cameron and Jacobovici surmise a seismic event which caused the land level to rise in Nuweiba, and subsequently sent a tsunami from the Red Sea northwards to drown the Egyptian army. Such a seismic event is nothing far-fetched, as a tectonic plate margin (between the Arabian and African plates) runs right through the Gulf of Aqabah. Note that the volcano mentioned in Exodus Decoded (Santorini) is located on the margin of the African and Eurasian plates.

The Egyptian peninsula, at the eastern side of the Gulf of Suez, is also called Sinai peninsula, because Christian archeologists long believed mount Sinai to be located on the Egyptian peninsula (instead of on the Arabian peninsula). A tectonic strike-slip fault runs through the Gulf of Aqabah. Southwards, the fault runs through the Red Sea, where its character becomes ‘constructive’, which means that the Arabian and African tectonic plates drift apart. If Moses’ hitting the water with his staff coincided with a seismic gap in the Red Sea, sea water from both the immediate north (Gulfs of Suez and Aqabah) and the immediate south (Gulf of Aden) would have flown into that gap, temporarily inducing a sea level drop in these three gulfs. The Indian Sea would eventually compensate for these level drops, in exchange for a slight drop in global sea levels; though not without a prior tsunami, originating from the Red Sea, and propagating through the three mentioned gulfs. This sequence of natural phenomena exactly coincides with what Moses ordered to be written down in the book of Exodus.

According to the Scripture (Exodus 3:18, Exodus 5:3, Exodus 8:27, Numbers 10:33) Moses initially required from Pharaoh the permission to march his people three days into the wilderness, in order to worship the Lord. If Moses had taken the Highway route, Pharaoh’s sentinels would have told him already the first day of their exodus that Moses did not seem to plan on worshiping his God in the wilderness. Pharaoh might have waited a few days to ascertain Moses’ moves. Along the so-called ‘exodus highway’, the Egyptian army could have joined Moses long before he could have reached what Rudd supposes is the biblical Pi Hahiroth (the southern most tip of the Sinai peninsula). That is enough of a reason, for me, to discard Rudd’s hypothesis. This criticism does not apply to the Wyatt/Fritz route. As it leads straight to the wilderness, the sentinels could only have reported a deviation from Moses’ plans on the fourth day of his exodus. The sentinels would have easily made it back to Pharaoh on the sixth day. For a fully mobilized chariot army to catch up with Moses through the wilderness, however, is a whole different story. No highway there. Chariots are five times as fast on flat terrain, but they become a true hindrance in the mountains. Hence, chariots and infantry probably marched together. A trained infantry might move twice as fast as Moses’ people, even when hurrying and ‘in military formation’ (Numbers 33:1). Consequently, it is quite reasonable to assume that the Egyptian army would have caught up with the Israelites in what Wyatt supposes to be the biblical Etham (14th day of the exodus). The army would have blocked their way north-east towards Ezion-geber (presently el-Aqabah, from which the gulf takes its name), upon which Moses was compelled to turn back abruptly (Exodus 14:2), and to proceed southwards, into even higher mountains. Four days later, Moses might have seen Nuweiba, in a strenuous marching effort. Quite understandably, once on the Nuweiba beach, the Israelites panicked (Exodus 14:10-14) — in front of them the ‘Sea of Reeds’ (known today as the gulf of Aqabah), and at their backs, the full Egyptian army, ready to deploy both infantry and cavalry.

There are a few more archeological finds which corroborate Wyatt’s hypothesis.

Some 480 years later, in the 10th century BC, King Solomon planted two commemorative columns at both sides of the sea crossing: Nuweiba beach on the Sinai peninsula, and Ras Dabr (called Baal-zephon in Exodus and Numbers) in Saudi Arabia. The text on the column on the Egyptian side has obviously been erased by the Egyptians: the granite column is polished like a mirror. The text on the column on the Arabian side was still legible. However, when Wyatt discovered it in 1978, the Arabian authorities swiftly removed the column (anxious as they are, as the Egyptians, to avoid eventual Israelite claims) and only marked the site. Wyatt claims the inscriptions on the column of Ras Dabr contain the words: Mizram (Egypt), death, water, pharaoh, Edom, Yahweh, and Solomon. I never heard this claim to be false.

King Solomon’s commemorative column at Nuweiba; the gulf of Aqabah is visible on the horizon |

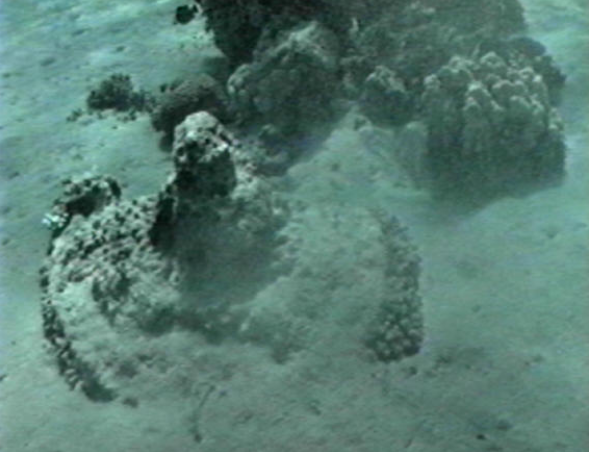

A chariot wheel photographed by Ron Wyatt on the sea bottom nearby Nuweiba, and right above it, possibly, the chariot cab |

Second, Wyatt claims to have found chariot remains on the bottom of the crossing. Rudd correctly points out that chariots float, as they are built of wood. However, it cannot be excluded that the tsunami buried chariots under a load of sand, that the wood gradually decomposed, gave rise to all kinds of marine life, and that only the gold coatings survived the ages. Those would be fragile indeed, and Wyatt claims that that was the very reason he would not try to bring them up.

A third reason is not of an archeological nature, and regards Rudd’s objection that the route from Ras Dabr (shore opposite to Nuweiba) to Jabal al-Lawz (the highest mountain peak in North-Western Saudi Arabia) is too long to fit the biblical narrative. However, this criticism only applies to what Rudd believes would have been Moses’ route, had he passed the Sinai wilderness instead of its highway along the Suez Canal. The second camp at the Sea of Reeds (Numbers 33:10) might have been on the gulf of Aqabah, too. The exact locations of the places mentioned in Numbers 33: 11-37 not being known with certainty, a much shorter route than the one proposed by Glen Fritz is possible.

It is remarkable that even highly educated academicians believe the Bible should not be read as an historical document, and worse, that it does not mean to provide any details concerning Moses’ route. For their information, here are the camp locations mentioned in Numbers 33: Succoth; Baal-zephon; Migdol; Pi-hahiroth; Etham; Marah; Elim; Dophkah; Alush; Rephidim; the wilderness of Sinai; Kibroth-hattaavah; Hazeroth; Rithmah; Rimmon-perez; Libnah; Rissah; Kehelathah; Mount Shepher; Haradah; Makheloth; Tahath; Terah; Mithkah; Hashmonah; Moseroth; Bene-jaakan; Hor-haggidgad; Jotbathah; Abronah; Ezion-geber; the wilderness of Zin (that is, Kadesh); Mount Hor, on the edge of the land of Edom; Zalmonah; Punon; Oboth; Iye-abarim, in the territory of Moab; Dibon-gad; Almon-diblathaim; the mountains of Abarim, before Nebo; the plains of Moab by the Jordan at Jericho; the Jordan from Beth-jeshimoth; Abel-shittim in the plains of Moab. Do not fear ye ‘objective scientists’: all these names are probably nothing but symbols. Please send me an email when you found out what exactly you believe they symbolize!

And as far as the mountain of Moses is concerned: one does not need to be an expert in Egyptology, nor in Israelitology, to understand that God does not select a minor mountain peak, to hand Moses the Stone Tablets.